Testing Significance on Paired Measurements: What Can Go Wrong?

What are pairs of measurements?

Measurement pairs of the form \((x_1, x_2)\) arise in two scenarios:

- Two measurements are performed for the same entity. For example, a clinical study evaluating the efficacy of a new form of insulin would measure blood glucose levels two times for every patient: before (\(x_1\)) and after taking the drug (\(x_2\)).

- Measurements are performed for different entities. However, entities are matched according to their characteristics. For example, to test the efficacy of a drug, you may want to pair study participants according to weight, age, or other characteristics in order to control for these confounding factors.

In the first case, the pairing is a natural consequence of the data generation process. In the second case, the pairing is enforced by the design of the study.

Why are dependent measurements helpful?

Using paired measurements, it is possible to control for confounding factors that influences the measured outcome. Matched study designs are therefore generally more powerful than designs involving independent groups.

The sleep data set

Let’s consider the sleep data set, to exemplify this:

data(sleep)

print(sleep)## extra group ID

## 1 0.7 1 1

## 2 -1.6 1 2

## 3 -0.2 1 3

## 4 -1.2 1 4

## 5 -0.1 1 5

## 6 3.4 1 6

## 7 3.7 1 7

## 8 0.8 1 8

## 9 0.0 1 9

## 10 2.0 1 10

## 11 1.9 2 1

## 12 0.8 2 2

## 13 1.1 2 3

## 14 0.1 2 4

## 15 -0.1 2 5

## 16 4.4 2 6

## 17 5.5 2 7

## 18 1.6 2 8

## 19 4.6 2 9

## 20 3.4 2 10extra indicates the increase/decrease (positive/negative values) in sleep compared to the baseline measurement, group denotes the drug, and ID gives the patient ID. To make this clearer, I’ll rename group to drug:

colnames(sleep)[which(colnames(sleep) == "group")] <- "drug"Investigating the sleep data set

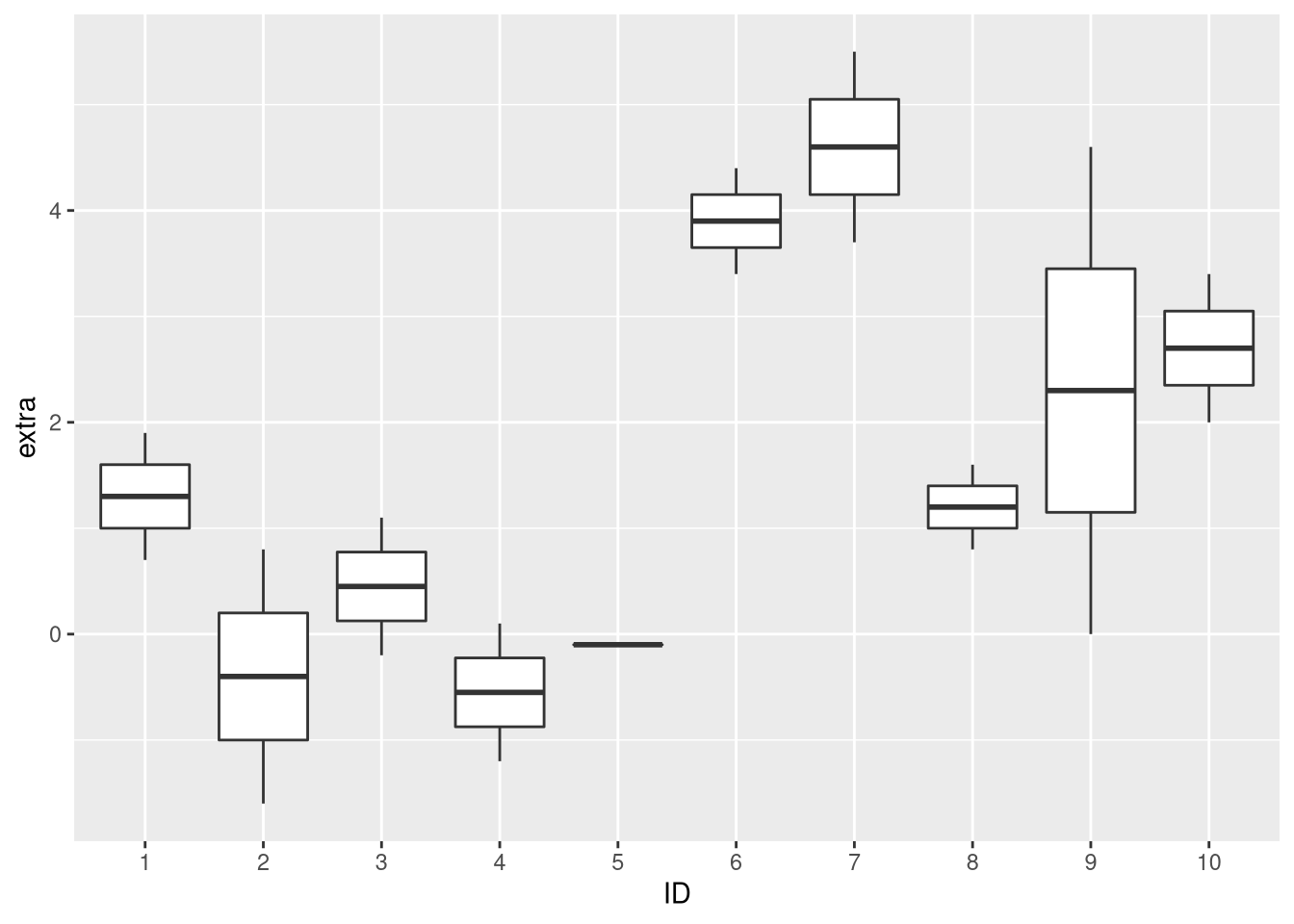

It is important to note that every person is different. Thus, the efficacy of the same drug may vary greatly from one person to another. Let’s see if this is also the case in this data set:

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(sleep, aes(x = ID, y = extra)) + geom_boxplot()

Indeed, the distribution of extra sleep time for the individual study subjects seems bimodal. About one half of the subjects exhibits large increases in sleep duration for both drugs, while the other half exhibits little benefit or even suffers from the medication. Using a paired test, these inter-patient differences can be corrected for, while this is not possible with a test that assumes that the measurements are independent.

Comparing Unpaired and Paired Tests

Let’s now compare how unpaired tests and paired tests perform on the sleep data set.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

If we use the unpaired Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney U test) on the measurements, the test would generate the following order of drugs to determine significance:

# order sleep data by 'extra':

o <- order(sleep$extra)

# order drugs by increasing extra sleep time:

drug.order <- sleep$drug[o]

print(drug.order)## [1] 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 1 2 2 2

## Levels: 1 2As we can see, although underrepresented, drug 1 occurs several times in the top ranks. This is because, for those patients that responded well to both drugs, drug 1 also worked well. Since there is no clear separation in the extra sleep time in dependence on the drug, the test fails to become significant at the 5% level:

x <- sleep$extra[sleep$drug == 1]

y <- sleep$extra[sleep$drug == 2]

# use an unpaired test:

w.unpaired <- wilcox.test(x, y, paired = FALSE)

print(w.unpaired$p.value)## [1] 0.06932758Wilcoxon signed rank test

Considering the measurements as pairs is more meaningful because then the result of the test is not influenced by the drug susceptibility in individual subjects. We can see that when we compute the intra-patient extra sleep difference, the measure that is used for the unpaired Wilcoxon signed rank test:

# compute pairwise differences of extra sleep times for the drugs

diff <- x - y

print(diff)## [1] -1.2 -2.4 -1.3 -1.3 0.0 -1.0 -1.8 -0.8 -4.6 -1.4The non-positive differences clearly demonstrate that drug 1 is inferior to drug 2 across all study subjects. Since the Wilcoxon signed rank test is based on these differences, it finds that there’s a significant difference between the two drugs at a significance level of 5%:

# use a paired test:

w.unpaired <- wilcox.test(x, y, paired = TRUE)

print(w.unpaired$p.value)## [1] 0.009090698Conclusions

This example shows why grouped study designs are superior over study designs where measurements are independent. Of course, this is only the case if the data are evaluated using a test that accounts for the paired measurements. Otherwise, statistical power is lost and an actually significant result may be falsely deemed insignificant.

Comments

There aren't any comments yet. Be the first to comment!