Testing Independence: Chi-Squared vs Fisher's Exact Test

What are contingency tables?

Contingency tables provide the integer counts for measurements with respect to two categorical variables. The simplest contingency table is a \(2 \times 2\) frequency table, which results from two variables with two levels each:

| Group/Observation | Observation 1 | Observation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | \(n_{1,1}\) | \(n_{1,2}\) |

| Group 2 | \(n_{2,1}\) | \(n_{2,2}\) |

Given such a table, the question would be whether Group 1 exhibits frequencies with respect to the observations than Group 2. The groups represents the dependent variable because they depend on the observation of the independent variable. Note that it is a common misconception that contingency tables must be \(2 \times 2\); they can have an arbitrary number of dimensions, depending on the number of levels exhibited by the variables. Still, performing statistical tests on contingency tables with many dimensions should be avoided because, among other reasons, interpreting the results would be challenging.

The warpbreaks data set

To study tests on contingency tables, we will use the warpbreaks data set:

data(warpbreaks)

head(warpbreaks)## breaks wool tension

## 1 26 A L

## 2 30 A L

## 3 54 A L

## 4 25 A L

## 5 70 A L

## 6 52 A LThis is a data set with three variables originating from the textile industry: breaks describes the number of times there was a break in a warp thread, \(\text{wool} \in \{A, B\}\) describes the type of wool that was tested, and \(\text{tension} \in \{L, M, H\}\) gives the tension that was applied to the thread (either low, medium, or high). Each row in the data set indicates the measurements for a single loom. To account for the variability of different looms, 9 measurements were performed for each combination of wool and tension, the data set contains a total of \(9 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 = 54\) observations.

Goal of the analysis

We would like to identify whether one type of wool outperforms the other for different levels of tensions. To investigate whether we can find some evidence for differences, let’s take a look at the data:

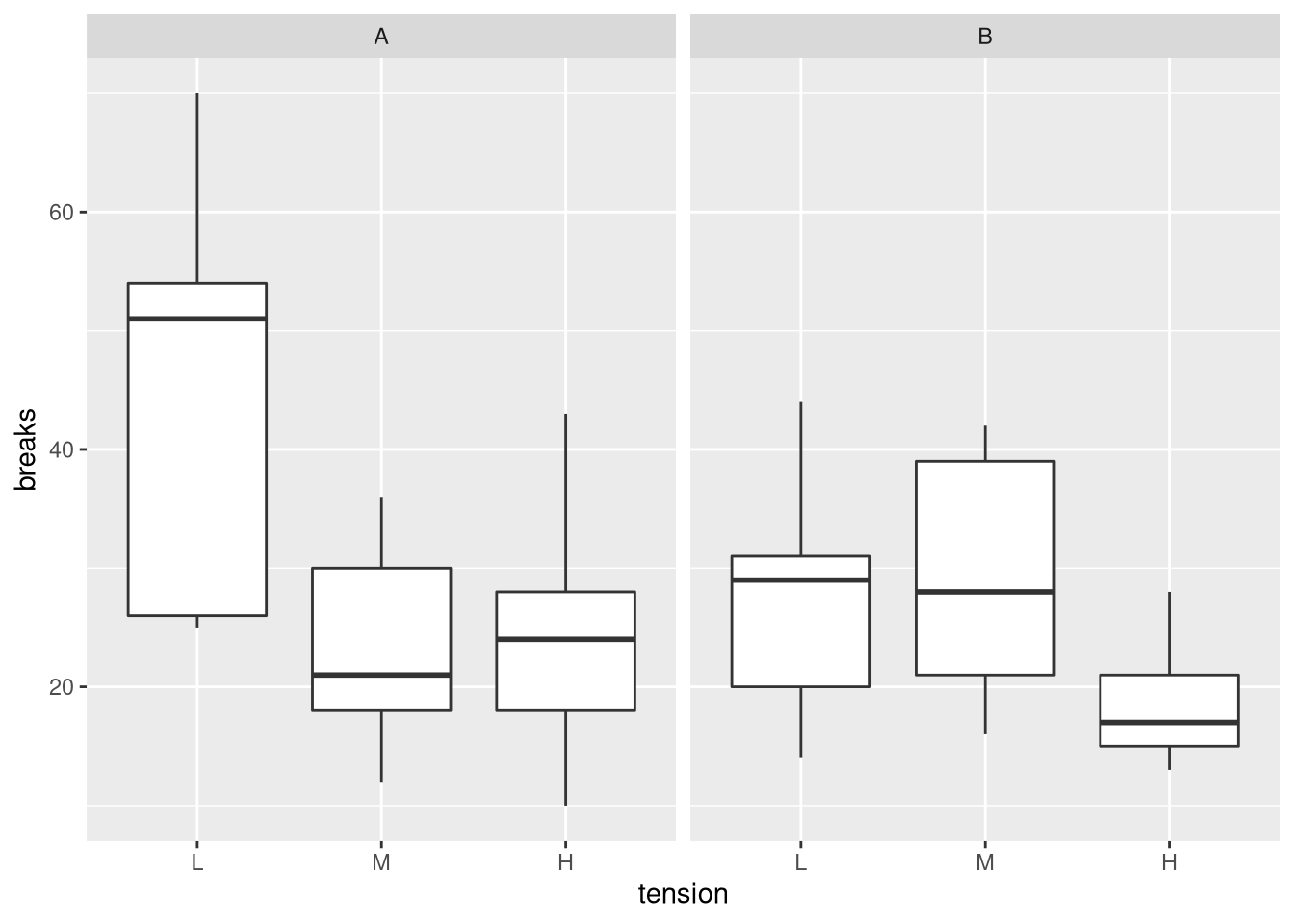

To investigate the differences in the number of strand breaks, let’s visualize the data:

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(warpbreaks, aes(x = tension, y = breaks)) + facet_wrap(. ~ wool) + geom_boxplot()

From the plot, we can see that, overall, wool B is associated with fewer breaks. Wool A seems to be particularly inferior for low tensions.

Transformation to contingency table

To obtain a contingency table, we first need to summarize the breaks across different looms for the two types of wool and the three types of tension.

library(plyr)

df <- ddply(warpbreaks, .(wool,tension), summarize, breaks = sum(breaks))

print(df)## wool tension breaks

## 1 A L 401

## 2 A M 216

## 3 A H 221

## 4 B L 254

## 5 B M 259

## 6 B H 169We then use the xtabs (pronounced as crosstabs) function to generate the contingency table:

df <- xtabs(breaks~wool+tension, data = df)

print(df)## tension

## wool L M H

## A 401 216 221

## B 254 259 169Now, df has the structure we need for applying statistical tests.

Statistical testing

The two most common tests for determining whether measurements from different groups are independent are the chi-squared test (\(\chi^2\) test) and Fisher’s exact test. Note that you should use McNemar’s test if the measurements were paired (e.g. individual looms could be identified).

Pearson’s chi-squared test

The \(\chi^2\) test is a non-parametric test that can be applied to contingency tables with various dimensions. The name of the test originates from the \(\chi^2\) distribution, which is the distribution for the squares of independent standard normal variables. This is the distribution of the test statistic of the \(\chi^2\) test, which is defined by the sum of chi-square values \(\chi_{i,j}^2\) for all pairs of cells \(i,j\) arising from the difference between a cell’s observed value \(O_{i,j}\) and the expected value \(E_{i,j}\), normalized by \(E_{i,j}\):

\[\sum \chi_{i,j}^2 \quad \text{where} \quad \chi_{i,j}^2 = \frac{(O_{i,j}−E_{i,j})^2}{E_{i,j}}\]

The intuition here is that \(\sum \chi_{i,j}^2\) will be large if the observed values considerably deviate from the expected values, while \(\sum \chi_{i,j}^2\) will be close to zero if the observed values agree well with the expected values. Performing the test via

chi.result <- chisq.test(df)

print(chi.result$p.value)## [1] 7.900708e-07Since the p-value is less than 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis of the test (the frequency of breaks is independent of the wool) at the 5% significance level. Based on the entries of df one could then claim that wool B is significantly better (with respect to warp breaks) than wool A.

Investigating the Pearson residuals

Another way would be to consider the chi-square values of the test. The chisq.test function, provides the Pearson residuals (roots) of the chi-square values, that is, \(\chi_{i,j}\). In contrast to the chi-square values, which result from squared differences, the residuals are not squared. Thus, residuals reflect the extent to which an observed value exceeded the expected value (positive value) or fell short of the expected value (negative value). In our data set, positive values indicate more strand breaks than expected, while negative values indicate less breaks:

print(chi.result$residuals)## tension

## wool L M H

## A 2.0990516 -2.8348433 0.4082867

## B -2.3267672 3.1423813 -0.4525797The residuals show that, compared with wool A, wool B had less breaks for low and high tensions than expected. For, medium tension, however, wool B had more breaks than expected. Again, we find that, overall wool B is superior to wool A. The values of the residuals also indicate that wool B performs best for low tensions (residual of 2.1), well for high tensions (0.41) and badly for medium tensions (-2.8). The residuals, however, helped us in identifying a problem with wool B: it does not perform well for medium tension. How would this inform further development? In order to obtain a wool that performs well for all tension levels, we would need to focus on improving wool B for medium tension. For this purpose, we could consider the properties that make wool A perform better at medium tension.

Fisher’s exact test

Fisher’s exact test is a non-parametric test for testing independence that is typically used only for \(2 \times 2\) contingency table. As an exact significance test, Fisher’s test meets all the assumptions on which basis the distribution of the test statistic is defined. In practice, this means that the false rejection rate equals the significance level of the test, which is not necessarily true for approximate tests such as the \(\chi^2\) test. In short, Fisher’s exact test relies on computing the p-value according to the hypergeometric distribution using binomial coefficients, namely via

\[p = \frac{\binom{n_{1,1} + n_{1,2}}{n_{1,1}} \binom{n_{2,1} + n_{2,2}}{n_{2,1}}}{\binom{n_{1,1} + n_{1,2} + n_{2,1} + n_{2,2}}{n_{1,1} + n_{2,1}}}\]

Since the computed factorials can become very large, Fisher’s exact test may not work for large sample sizes.

Note that it is not possible to specify the alternative of the test for df since the odds ratio, which indicates the effect size, is only defined for \(2 \times 2\) matrices:

\[OR = {\frac{n_{1,1}}{n_{1,2}}}/{\frac{n_{2,1}}{n_{2,2}}}\]

We can still perform Fisher’s exact test to obtain a p-value:

fisher.result <- fisher.test(df)

print(fisher.result$p.value)## [1] 8.162421e-07The resulting p-value is similar to the one obtained from the \(\chi^2\) test and we arrive at the same conclusion: we can reject the null hypothesis that the type of wool is independent of the number of breaks observed for different levels of stress.

Conversion to 2 by 2 matrices

To specify the alternative hypothesis and obtain the odds ratio, we could compute the test for the three \(2 \times 2\) matrices that can be constructed from df:

p.values <- rep(NA, 3)

for (i in seq(ncol(df))) {

# compute strand breaks for tested stress vs other types of stress

test.df <- cbind(df[, i], apply(df[,-i], 1, sum))

tested.stress <- colnames(df)[i]

colnames(test.df) <- c(tested.stress, "other") # for clarity

test.res <- fisher.test(test.df, alternative = "greater")

p.values[i] <- test.res$p.value

names(p.values)[i] <- paste0(tested.stress, " vs others")

}Since the alternative is set to greater, this means that we are performing a one-tailed test where the alternative hypothesis is that wool A is associated with a greater number of breaks than wool B (i.e. we expect \(OR > 1\)). By performing tests on \(2 \times 2\) tables, we also gain interpretability: we can now distinguish the specific conditions under which the wools are different. Before interpreting the p-values, however, we need to correct for multiple hypothesis testing. In this case, we have performed three tests. Here, we’ll simply adjust the initial significance level of 0.05 to \(\frac{0.05}{3} = 0.01\overline{6}\) according to the Bonferroni method. Based on the adjusted threshold, the following tests were significant:

print(names(p.values)[which(p.values < 0.05/3)])## [1] "L vs others"This finding indicates that wool B is only significantly superior to wool A if the stress is light. Note that we could have also the approach of constructing \(2 \times 2\) matrices for the \(\chi^2\) test. With the \(\chi^2\) test, however, this wasn’t necessary because we based our analysis on residuals.

Summary: chi-squared vs Fisher’s exact test

Here is a summary of the properties of the two tests:

| Criterion | Chi-squared test | Fisher’s exact test |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal sample size | Large | Small |

| Accuracy | Approximate | Exact |

| Contingency table | Arbitrary dimension | Usually 2x2 |

| Interpretation | Pearson residuals | Odds ratio |

Generally, Fisher’s exact test is preferable to the chi-squared test because it is an exact test. The chi-squared test should be particularly avoided if there are few observations (e.g. less than 10) for individual cells. Since Fisher’s exact test may be computationally infeasible for large sample sizes and the accuracy of the \(\chi^2\) test increases with larger number of samples, the \(\chi^2\) test is a suitable replacement in this case. Another advantage of the \(\chi^2\) test is that it is more suitable for contingency tables whose dimensionality exceeds \(2 \times 2\).

Comments

Hugo L.F.

28 Feb 20 10:51 UTC

Dear Matthias,

Thank you for this post. Why do you say that “chi-square test is more suitable for contingency tables greater than 2x2”? As far as I know, the Fisher’s exact test also works with such tables. Is there any statistical reason for choosing chi-square in these cases?

Thanks in advance,

Matthias

13 Mar 20 10:39 UTC

simulate.p.value=TRUEwhen callingfisher.test). Of course, this shouldn’t stop you from using the test if you expect that a non-parametric test is more appropriate.