The SOLID Principles: a Guide for Object-Oriented Design

For designing object-oriented software, five principles have emerged over the years. These principles are summarized by the acronym SOLID, which stands for:

- S: The single-responsibility principle

- O: The open-closed principle

- L: The Liskov substitution principle

- I: The interface segregation principle

- D The dependency inversion principle

In this post, I aim to give a succinct summary of the principles together with practical examples on how to apply them.

1. The Single-Responsibility Principle

According to the single-responsibility principle, each class should have only a single responsibility. This principle is one of the foundations for good object-oriented design:

- It fosters object reuse and replaceability

- It enables delegation of work to other objects

- It improves the structure of the code, allowing for further improvements (e.g. use of design patterns)

To apply the single-responsibility principle, you should consider the responsibilities of each class you are implementing. When you realize that a class has more than one responsibility, you should move these additional responsibilities to other classes.

Applying the Single-Responsibility Principle

Let’s consider the example of a bike rental system. The idea is that registered customers should be able to rent a bike. Then they can unlock the bike and drive around. Upon returning the bike, the duration of the lease is calculated and an invoice, whose amount depends on the lease duration, is generated. Finally, the bike is locked one again and becomes available for other customers.

To implement this software system, we’ll use the following class to represent a bike that can be leased:

class Bike {

public:

void lock(); // prevent physical access to the bike

void unlock(); // allow physical access to the bike

void startLease(Customer customer); // prevent other customers from leasing the bike

void endLease(); // make the bike available to other customers again

double calculateCosts(); // how much does the customer have to pay?

void addInvoice(); // add invoice to customer account

Invoice createInvoice();

private:

int leaseDurationSeconds; // how long the bike has been on lease

bool isLocked; // whether the bike is currenty locked

Customer leasingCustomer; // details of customer leasing the bike

};How does the Bike class fare with respect to the single-responsibility principle? Looking at the Bike class, I see three responsibilities:

- The

lockandunlockmethods control physical access to the bike - The

startLeaseandendLeasemethods provide functionality for leasing - The

calculateCostsandsendInvoiceare used for accounting

To reduce the number of responsibilities, let’s introduce the following (modified/new) classes:

- The

Bikeclass should only model the physical properties of the bike - A

Leaseclass should deal with lease-specific information - An

InvoiceGeneratorclass should deal with the accounting

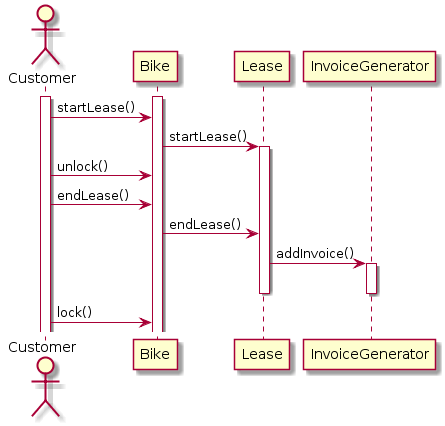

The sequence diagram for the redesigned bike rental scheme would look like this:

To implement, the new design, we’ll start with declaring the Lease class:

class Lease {

public:

void startLease(Customer customer);

void endLease();

private:

Customer leasingCustomer;

InvoiceGenerator invoice;

Time leaseStart;

Time leaseEnd;

};The idea is that the lease class is used to register/deregister the customer that is leasing a bike. Since every lease should result in an invoice, the lease class contains an InvoiceGenerator object, which performs all accounting tasks. The InvoiceGenerator can be written as follows:

class InvoiceGenerator {

public:

void setLeaseDuration(int leaseDurationSeconds);

void setCustomer(Customer customer);

void addInvoice(); // register invoice with customer

Invoice createInvoice();

private:

int leaseDurationSeconds;

int dollarCostsPerSecond = 0.001;

Customer customer; // customer data such as name, address, ...

double calculateCost(); // cost of lease

};With these two classes prepared, we can simplify the Bike class:

class Bike {

public:

void lock();

void unlock();

void startLease(Customer customer);

void endLease();

private:

bool isLocked;

Lease lease;

};Notice that the bike class is now much simpler because it doesn’t have to provide the accounting functionalities anymore.

Having redesigned the classes, let’s take a look at the implementation of these classes. For bike, the implementation is as follows.

void Bike::lock() {

// (logic for locking the bike)

isLocked = true;

}

void Bike::unlock() {

// (logic for unlocking the bike)

isLocked = false;

}

void Bike::startLease(Customer c) {

lease.startLease(c)

}

void Bike::endLease() {

lease.endLease()

}Lease could be implemented like this:

void Lease::startLease(Customer c) {

// (additional logic for starting the lease)

leasingCustomer = c;

invoice.setCustomer(c);

leaseStart = time::now();

}

void Lease::endLease() {

// (additional logic for ending the lease)

leaseEnd = time::now();

int leaseDuration = (leaseEnd - leaseStart).inSeconds();

invoice.setLeaseDuration(leaseDuration);

leasingCustomer = null;

}Now, the only that’s left is the implementation of the InvoiceGenerator class:

void InvoiceGenerator::setLeaseDuration(int leaseDuration) {

leaseDurationSeconds = leaseDuration;

}

void InvoiceGenerator::setCustomer(Customer c) {

customer = c;

}

double InvoiceGenerator::calculateCost() {

return leaseDurationSeconds * dollarCostsPerSecond;

}

Invoice InvoiceGenerator::createInvoice() {

double cost = calculateCost();

HTMLDocument invoice = HTMLDocument("<HTML>\n" + "Name : " + customer.getName() + "\nNet Amount: " + cost + " ... "\n</HTML>");

return invoice;

}

void InvoiceGenerator::addInvoice() {

customer.addInvoice(createInvoice());

}As you can see, having introduced the additional classes Lease and InvoiceGenerator, individual objects can often dispatch work to those objects whose responsibility lies in performing a specific task. Moreover, with the new design, we are prepared for extending the functionality of our program. For example, since we have an InvoiceGenerator class, it would be easy to implement other types of invoices rather than HTML invoices.

2. The Open-Closed Principle

The open-closed principle states that software should be open for extension but closed to modification. When I first heard this principle, it sounded like an oxymoron to me: how can software be extensible but closed for modification? Doesn’t every extension require modification?

What the open-closed principle tries to say is that, if you want to extend the functionality of your software, you shouldn’t have to modify existing building blocks of the software (i.e. the software is closed for modification). Instead, new functionality should be introduced through new entities (i.e. the software is open for extension).

One way to come closer to implementing the open-closed principle is to follow the guideline of

Encapsulate what variesThis guideline states that code elements that are subject to variation throughout software development should be encapsulated in appropriate classes.

Note that the open-closed principles is one of the principles that you shouldn’t apply to all of your code because this would lead to overengineered software with unnecessary abstractions. Instead, you should focus your effort on those building blocks for which you can expect some degree of change in the future.

Applying the Open-Closed Principle

To study the open-closed principle in practice, let’s study the InvoiceGenerator class from the previous bike rental example.

class InvoiceGenerator {

public:

void setLeaseDuration(int leaseDurationSeconds);

void setCustomer(Customer customer);

void invoice();

private:

int leaseDurationSeconds;

int dollarCostsPerSecond = 0.001;

Customer customer;

double calculateCost();

};Here, the createInvoice() method generates the invoice as an HTML document. In our case, we would like to use Comic Sans MS for all customers whose age is less than 14 and Arial for all others. Because we don’t want to modify the createInvoice() method to implement the new behavior, we will refactor InvoiceGenerator in order to satisfy the open-closed principle.

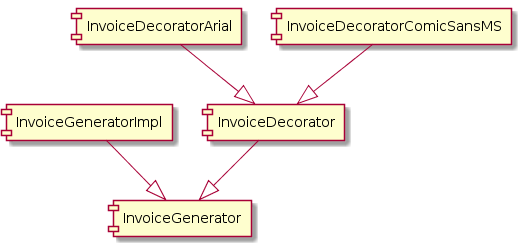

One way to achieve this is to use the decorator pattern. By applying this pattern, we can modify the style of the generated invoice by introducing decorator classes. To implement the pattern, we turn InvoiceGenerator into an abstract class and let InvoiceDecorator implement the InvoiceGenerator interface:

The new design results in the following classes:

class InvoiceGenerator {

public:

void setCustomer(Customer customer);

void setLeaseDuration(int leaseDurationSeconds);

virtual void createInvoice() = 0;

private:

Invoice invoice;

int leaseDurationSeconds;

int dollarCostsPerSecond = 0.001;

Customer customer;

double calculateCost();

};

class InvoiceGeneratorImpl : InvoiceGenerator {

public:

void createInvoice() override;

};

class InvoiceDecorator : InvoiceGenerator {

public:

InvoiceDecorator(InvoiceGenerator invoiceGenerator);

private:

InvoiceGenerator generator;

};

class InvoiceDecoratorComicSansMS: InvoiceDecorator {

public:

Invoice createInvoice();

};

class InvoiceDecoratorArial: InvoiceDecorator {

public:

Invoice createInvoice();

};We can now specify the basic behavior of the invoice generator using InvoiceGeneratorImpl. Furthermore, we define the decorators for modifying the font.

InvoiceGeneratorImpl::createInvoice() {

// create the basic invoice structure, e.g. like so

invoice.setContent("<HTML> " + "Name : " + customer.getName() + ", Net Amount: " + cost + " ... " + "</HTML>");

}

InvoiceDecoratorComicSansMS::createInvoice() {

invoice.setFont("ComicSansMS");

if (generator != null) {

generator.createInvoice();

}

}

InvoiceDecoratorArial::createInvoice() {

invoice.setFont("Arial");

if (generator != null) {

generator.createInvoice();

}

}With the new design, InvoiceGeneratorImpl::createInvoice() is closed for modification but remains open for extension because new functionality can be added without changing the createInvoice method. Rather, we can simply instantiate a decorator and use that decorator to modify the behavior of InvoiceGeneratorImpl.

Let’s see how we can change the font of the invoice through the new font decorators:

InvoiceGenerator invoiceGenerator = InvoiceGeneratorImpl();

if (customer.age < 14) {

// use comic sans ms for the invoice

invoiceGenerator = InvoiceDecoratorComicSansMS(invoiceGenerator);

} else {

// use arial for the invoice

invoiceGenerator = InvoiceDecoratorArial(invoiceGenerator);

}

// ... use 'invoiceGenerator' to create fancy invoicesWith the new design, we can simply implement new decorators to meet additional layout needs (e.g. for adjusting font size or background color) - all without having to do any changes to the createInvoice method.

3. The Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov substitution principle states that derived classes should not modify the behavior of the superclass. In more lax terms, the Liskov substitution principle states that

A duck should look like a duck, swim like a duck, and quack like a duck. Otherwise it's not really a duck.Applying the Liskov Substitution Principle

Let’s make the Liskov substitution principle more concrete with an example. Imagine you have a class for rectangles:

class Rectangle {

public:

void setWidth(int w) {

width = w ;

}

void setHeight(int h) {

height = h;

}

private:

int width;

int height;

};The respective invariants of the setWidth and setHeight methods are that only the width or only the height of the rectangle are set.

Imagine that you would also like to have an implementation for squares. Squares are a special type of rectangle where the width equals the height. Since squares have the same attributes as rectangles, you decide to derive from the rectangle class. To uphold the invariant of the square, you have to adjust the setWidth and setHeight methods as follows:

class Square : Rectangle {

public:

void setWidth(int w) {

width = w;

// also set height s.t. height = width

height = w;

}

void setHeight(int h) {

height = h;

// also set width s.t. width = height

width = h;

}

};What’s the problem with the implementation of Square? In fact, Square modifies the behavior of the inherited methods from Rectangle: setWidth and setHeight always change both width and height.

This means that the substitution principle is broken: due to the changed behavior of Square you cannot treat it the same way as Rectangle. Thus, we should never have subclassed Rectangle to create a Square class in the first place but should have created a custom Square class instead.

4. The Interface Segregation Principle

The interface segregation principle states that a client should not be forced to implement superfluous interface methods. This means that smaller interfaces (i.e. interfaces providing few methods) should be favored over larger interfaces (i.e. interfaces providing many methods).

Software fulfilling the interface segregation principle will be easier to maintain. First, the software will be more understandable because smaller interfaces communicate the intent better. Second, it will be less burdensome to extend a lean interface that is implemented by few classes than to extend a bloated interface that is implemented by many clients.

Applying the Interface Segregation Principle

To illustrate the interface segregation principle, let’s consider a rental agency as an example. To represent the objects we rent out, let’s create an interface Rentable. At first, we have a lean interface requiring only the implementation of two methods:

class Rentable {

public:

virtual void startLease() = 0;

virtual void endLease() = 0;

};After implementing the interface, we quickly realize that we need new functionality, namely:

- For battery-driven products (e.g. smartphones), we would like to know the capacity of the built-in battery

- For products with age restrictions (e.g. DVDs, computer games), we would like to know the minimum age required to be allowed to rent these items

- For clothes, we would like to know the size of the piece of clothing

Since we already have the Rental interface, we do a very lazy and dumb thing: put all of these methods into the interface. So the new interface looks like this:

class BloatedRentable {

public:

virtual void startLease() = 0;

virtual void endLease() = 0;

virtual int getBatteryCapacity() = 0; // for battery-driven devices only

virtual int getAgeLimit() = 0; // for age-limited products only

virtual int getSize() = 0; // for clothes only

};Why is this bad design? Well, look what happens when we want to implement a class for jeans:

class BloatedJeans : BloatedRentable {

void startLease {

// start lease logic

}

void endLease {

// end lease logic

}

int getBatteryCapacity() {

// no battery in most jeans, let's return something unusual

return -1;

}

int getAgeLimit() {

// no age limit on jeans

return 0;

}

int getSize() {

return size;

}

};There are two things that are wrong with the BloatedJeans class. The first problem is that we have to waste time implementing methods such as getBatteryCapacity() and getSize() that we don’t need. The second problem is that a client using the BloatedRentable interface has to deal with the (nonsensical) values that are returned for inappropriate method calls. For example, the client would have to ignore all results from getBatteryCapacity where the value is negative because this indicates that the method was called on an inappropriate object.

To illustrate the hassle that the client has to go through, let’s assume the client wants to count the different types of wearable objects that are in stock:

void printWearableCount() {

int nbrOfWearables = 0;

for (BloatedRentable r: rentables) {

if (r.getSize() >=0) {

// assume this is a wearable

++nbrOfWearables;

}

}

std::cout << "No of wearables: " << nbrOfWearables;

}How can we improve our design? Let’s apply the interface segregation principle. To do this, we keep the Rentable interface lean and create interfaces for specific rentable items:

// interface to be implemented by all rentable objects

class LeanRentable {

public:

virtual void startLease() = 0;

virtual void endLease() = 0;

};

// interface to be implemented by all battery-driven devices

class Chargeable {

public:

virtual int getBatteryCapacity() = 0;

};

// interface to be implemented by all age-limited products

class AgeLimited {

public:

virtual int getAgeLimit() = 0;

};

// interface to be implemented by all pieces of clothing

class Wearable {

public:

virtual int getSize() = 0;

};With these lean interfaces we can now implement the class for rentable jeans as follows:

// Jeans are both a rentable and a wearable

class LeanJeans : LeanRentable, Wearable {

void startLease {

// logic for starting the lease (LeanRentable interface)

}

void endLease {

// logic for ending the lease (LeanRentable interface)

}

int getSize() {

// method from the Wearable interface

return size;

}

};The implementation of LeanJeans was already much easier than the one of BoatedJeans because we had to implement fewer methods. What about the client though? Let’s revisit our method for printing the number of wearables in stock:

void printWearableCount() {

int nbrOfWearables = 0;

for (LeanRentable* r: rentables) {

Wearable* w =

if (std::dynamic_cast<Wearable*>(r)) {

// cast was successful -> r is a wearable

++nbrOfWearables;

}

}

std::cout << "No of wearables: " << nbrOfWearables;

}With the new implementation, the client has less hassle. To count the number of wearables in stock, we can rely on the object’s type rather than on some inherent assumptions.

5. The Dependency Inversion Principle

The dependency inversion principle is often misunderstood. One reason for this is that the name of the principle is not really very informative. What is meant by dependency inversion?

In conventional software design, high-level modules often depend on low-level modules. So, what happens if we invert this design scheme? Then, we would have low-level modules depend on high-level modules and high-level modules would be independent of low-level modules. This is the essence of the dependency inversion principle, which states the following:

- Both high-level and low-level modules should depend on abstractions.

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

Applying Dependency Inversion to Module Dependencies

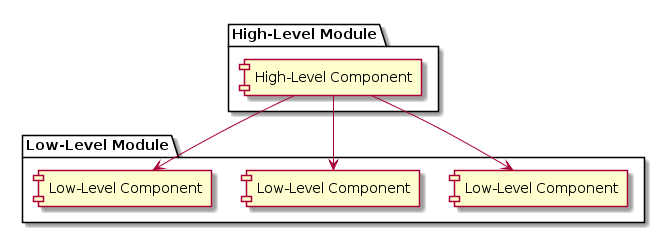

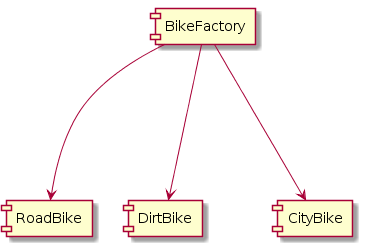

This example demonstrates the first aspect of the dependency inversion principle, which states that both high- and low-level modules should depend on abstractions. A traditional dependency structure would be as follows:

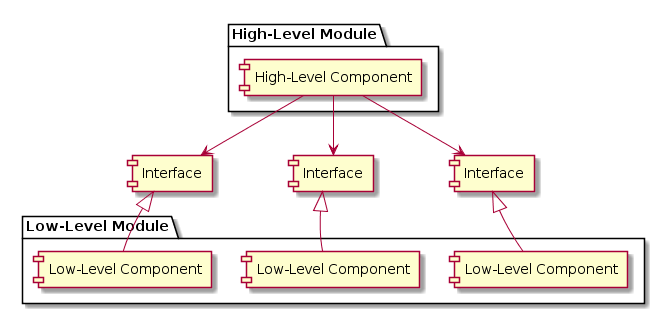

Here, the high-level module depends directly on low-level components. This means that there is strong coupling, with all its disadvantages. Applying the dependency-inversion principle, we would obtain the following dependency structure:

Here, the high-level module depends on abstraction (interfaces) rather than concrete implementations. Since the low-level modules implement interfaces, they also depend on abstractions.

Applying Dependency Inversion to Abstractions

This example demonstrates the second aspect of the dependency inversion principle, which states that abstractions should not depend on details but that details should depend on abstractions.

Let’s consider an example where the principle is not fulfilled, that is, where abstractions depend on details. Let’s assume we are concerned with bikes. To encapsulate the creation of different types of bikes, we create a class BikeFactory, which generates objects of the concrete classes RoadBike, DirtBike, and CityBike:

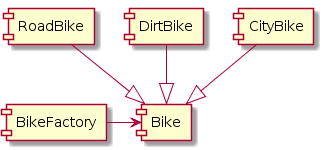

To apply the dependency inversion principle, we create a Rentable interface that is implemented by each type of bike. Then, the factory can simply generate objects of type Rentable:

The new design fulfills the dependency inversion principle because the details (i.e. the specific types of bikes) depend on abstractions (Bike), rather than the other way around.

Summary

At the end of this article, I would like to shortly summarize how each of the five SOLID principles can be applied in practice:

- Single-responsibility principle: Each class should only have a single responsibility. If you see a class with many lines of code, this can be an indicator that the class serves more than one responsibility.

- Open-closed principle: Extending the functionality of your software shouldn’t require you to modify (a lot) of existing code. If you have to modify (several) existing files to extend functionality, you are probably not following the open-closed principle. To satisfy the open-closed principle, think about appropriate design patterns for your problem.

- Liskov substitution principle: The behavior of subclasses should not deviate from the behavior that is implemented by the superclass. So, when you are overriding a method of the superclass, make sure that you are not breaking the invariants of the superclass. If that would be the case, use of inheritance is not appropriate.

- Interface segregation principle: To implement the interface segregation principle, don’t lump different types of functionality in the same interface. Instead, try to write lean interfaces.

- Dependency inversion principle: The dependency inversion principle can be satisfied by coding against interfaces rather than concrete implementations.

Comments

There aren't any comments yet. Be the first to comment!